Catharism was the greatest heretical challenge faced by the Catholic Church in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The attempt by the Cathars to find an answer to the fundamental religious and philosophical problems posed by the existence of evil, combined with their success in persuading large numbers of Christians in the West that they had solved these problems, shook the Catholic hierarchy to its very core, and provoked a series of reactions more extreme than any previously contemplated

Malcolm Barber – The Cathars: Dualist Heretics in Languedoc in the High Middle Ages

OK a head’s up for those of a sensitive or nervous disposition. This blog has almost nothing to do with a) the proliferation of the ‘wokerati’ in modern society b) recent sexual scandals involving the Church of England or c) Brexit. However, in so far as its traditional in polite society not to discuss politics, religion or sex, this blog may be slightly shocking! Forewarned is forearmed.

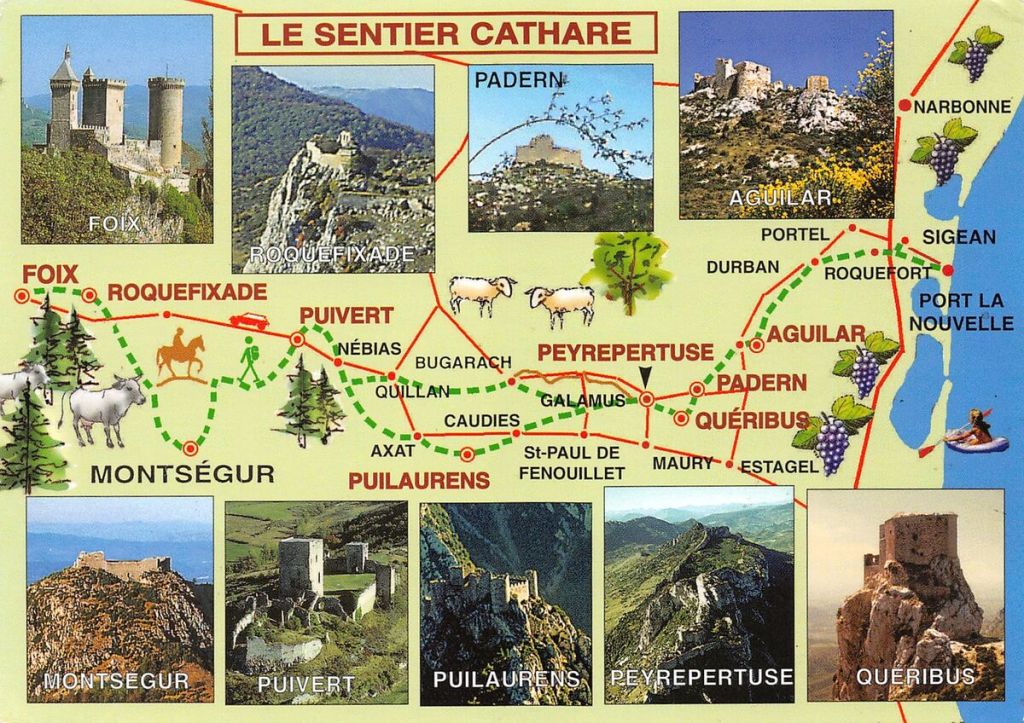

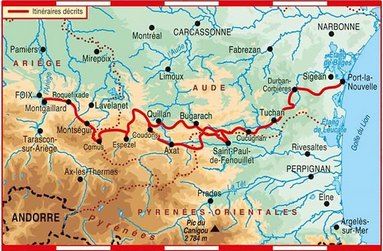

The day after tomorrow (Wednesday) I’m heading off on the 240km Sentier cathare (GR367) and planning to walk from Port-la-Nouvelle on the Mediterranean to Foix in the Ariège in a week. As ever, I’ve done pretty much zero preparation for the walk apart from a couple of gentle dog walks with Puzzle. I’ve got a new pair of boots but what I may need is a new pair of hips! Let’s see how the next week goes. In the meantime, for those of you who don’t know much about the Cathars, read on!

Forty years ago, almost to the day, I was ensconced in the Examination Halls of Oxford University sitting my Finals and grappling with abstruse questions on obscure topics of English and European History. Amongst the subjects I had chosen to specialise in were ‘Byzantium in the Age of Constantine Porphyrogenitus’ and ‘The Crusades’. Tutorials for the latter were led by a fresh faced post doctoral student at Exeter College by the name of Christopher Tyerman, subsequently perhaps the most eminent historian of the Crusades.

It was in his rooms at Exeter College, that I first learnt about the Albigensian/Cathar Crusade which took place in the 13th century and was primarily focussed on the Languedoc region of France where I currently live. Forty years on, I can scarcely believe that I am about to set out on a 240 km walk retracing the events of the Albigensian Crusade along the Cathar Way (GR367).

Christopher Tyerman assumed the mantle of Sir Steven Runciman, Old Etonian, pre-eminent historian of the Crusades and Manichaeism, friend of Cecil Beaton, tutor of Guy Burgess, and amongst much else, Grand Orator of the Orthodox Church, a member of the Order of Whirling Dervishes, Greek Astronomer Royal and Laird of Eigg! He was a fascinating character and his biography is well worth a read! But I digress. Back to the Cathars.

Who were the Cathars?

For those who’d like to learn more about the Cathars and don’t want to wade through my long winded musings on the subject, attached is a link to an episode of In Our Time with Melvyn Bragg: In Our Time – Catharism – BBC Sounds. Alternatively you can always listen to The Rest is History podcast ‘The Mystery of the Cathars’ with Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook which will leave you thoroughly confused as it attempts to debunk the bulk of what follows, claims that the Cathars didn’t really exist at all and were largely the figment of the Roman Catholic Church’s paranoid fears of heresy! 302: The Mystery of the Cathars • The Rest Is History. They argue that the whole Cathar saga (based partly on the fact that none of the supposed heretics ever referred to themselves as Cathars and the links between dualism, Bogomils and the Cathars is pretty tenuous)) is as genuine as a Dan Brown or Kate Mosse blockbuster!

The Cathars (from Greek katharos/καθαρός, “pure” the same stem as catharsis and cathartic) were an heretical Christian sect that flourished in western Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries. The Cathars professed a neo-Manichaean dualism – that there are two principles, one good and the other evil, and that the material world is evil. Similar views were held in the Balkans and the Middle East by medieval religious sects including the Paulicians and the Bogomils with whom the Cathars were connected.

The logical problem of evil

The Bogomils (trans – lovers of God), like the Cathars had a problem. How to explain the nature of the world? The Church taught that God is the source of all perfection and that the whole world, visible and invisible, is His creation. Yet you don’t need to have a philosophy degree to observe that all in this world – suffering, cruelty, decay, death – is far from perfect. That raises the question of how can a benevolent omnipotent and omniscient God be the cause of both suffering and evil? Must He be held responsible for wars, epidemics, the oppression of the poor by the rich?… The Bogomils, as did the Cathars, had an answer to this conundrum which was at least logical and consistent: evil and pain are inherent in this world because this world is the creation of Satan. Clearly the Old Testament’s take on things (Man + Woman + Snake + Apple = Corruption = Fall from Grace & Exile from Paradise) didn’t hold water with the feminist vegan loving Cathars who saw it all as a bit of a con. Modern philosophers call this “the logical problem of evil”.

The first Cathars appeared in western Germany, Flanders and Italy in the early 11th century. Little was subsequently heard of them until they reappeared in the 12th century when they enjoyed a period of rapid growth fuelled by Bogomil missionaries and Western dualists returning from the Second Crusade (1147–49). From the 1140s the Cathars had become an organized church with a hierarchy, a liturgy, and a system of doctrine. The first Cathar bishoprics were established in the north of France followed by Albi and Lombardy.By the turn of the century there were eleven Cathar bishoprics in all, one in the north of France, four in the south, and six in Italy

What did the Cathars believe?

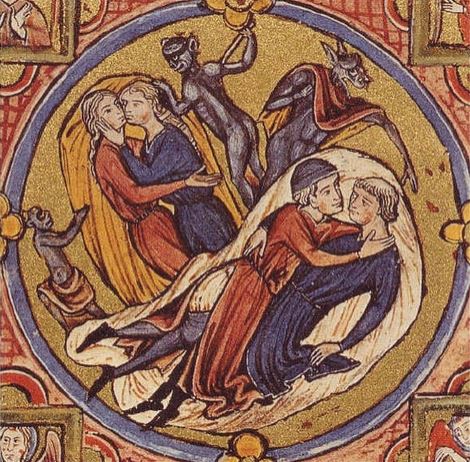

Although there were some differences in their beliefs, all Cathars agreed all mankind was trapped in the bodies of angels who had been deceived by Satan who had engineered their fall from Heaven. Man’s purpose in life was to renounce the pleasures and enticements of life on earth (sex, meat etc) and through repeated incarnations, make his way back to heaven

Cathars rejected the teachings of the Catholic Church as immoral and viewed most of the books of the Bible as inspired by Satan. They rejected the Church for what they saw as the hypocrisy of the clergy as well as the Church’s acquisition of land and wealth.

Their extreme asceticism made the Cathars a church of the elect, and yet in France and northern Italy it became a popular religion. This success was achieved by the division of the faithful into two ranks: the “perfect” and the “believers.” The perfect were set apart from the mass of believers by a ceremony of initiation, the consolamentum. They devoted themselves to contemplation and were expected to maintain the highest moral standards. In contrast the believers were not expected to attain the same standards as the perfect.

Why did Catharism take hold in the south of France?

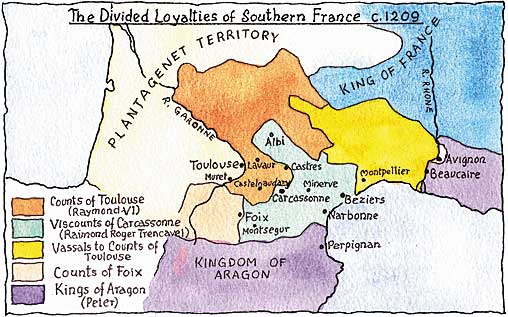

In the early Middle Ages Languedoc wasn’t really part of France. It was an independent area comprising a handful of city-states, each with its own rulers, the most powerful of whom were the Counts of Toulouse. During the 12th century, the Cathar religion flourished in this area noted for its culture, sophistication, religious tolerance and liberalism. The most highly educated people spoke Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, and Occitan, the language of the songs and poetry of the troubadours (travelling musicians). It was also a pretty remote region, far from the influence of the Pope or the French king.

By the turn of the 13th century, Catharism was the major religion in the Languedoc area of France. The Counts of Toulouse, among many other noble families, were either supporters of, or were Cathars themselves. The fact that the area was on the Mediterranean trade routes made it a cultural melting pot, where new ideas and different religious ideas were more readily embraced than in the cooler climes of northern Europe.

Why were the Cathars such a threat to the Catholic church in the early 13th century?

Cathars rejected the practices of communion, paying tithes, funeral rites and penances. They were strict about biblical injunctions – notably those about living in poverty, not killing, not telling lies nor swearing oaths. They believed in reincarnation, equality between the sexes, contraception, and veganism, and accepted euthanasia and suicide as part of life. Not surprisingly, they weren’t exactly flavour of the month with the Church authorities in Rome who regarded them as an existential threat to their authority!

The Albigensian Crusade

The Roman Catholic Church had attempted for years to root out the Cathar heresy from southern France, where it remained popular, particularly among the nobility. St Dominic, who was sent to the region to preach to the people and debate with Cathar leaders, formed his Order of Preachers (Dominicans) in response to the heresy. However, all efforts at eradication failed largely because of the tolerance towards the Cathars maintained by Count Raymond VI of Toulouse, the most powerful ruler in the region. Shortly after his excommunication for assisting Cathar heretics, Raymond was implicated in the murder of a papal legate, Pierre de Castelnau who had been sent by the Pope to investigate the situation.

For Innocent III that was the final straw. Exclaiming “These heretics are worse than the Saracens!”, in March 1208 he called for a Crusade against Raymond and the heretics of Languedoc, which began the following year. For forty days spent on Crusade, Crusaders would be rewarded with a full remission of sins and as much land and booty as they could seize from the Cathar heretics. Not surprisingly, hundreds of penniless knights across northern Europe answered Innocent III’s call to arms which conveniently ignored the parable that “it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God.”

Béziers was the site of one of the most brutal massacres in 1209 when as many as 10,000 of the town’s inhabitants were killed by the Crusaders. The local abbot advised the Crusaders not to worry too much about distinguishing the Cathar heretics from the innocent faithful, commanding them to “Kill them all, for the Lord knoweth them that are His” (Caedite eos. Novit enim Cominus qui sunt eius)

Simon de Montfort, the leader of the Crusade, was utterly ruthless, burning 140 Cathars in the village of Minerve. After taking prisoners from the village of Bram, he (reportedly) had their eyes gouged out and their ears, noses and lips cut off. One of these prisoners was blinded in one eye so that with the other he could lead all the other poor maimed prisoners to the next village, Lastours, as a warning to them about what was in store.

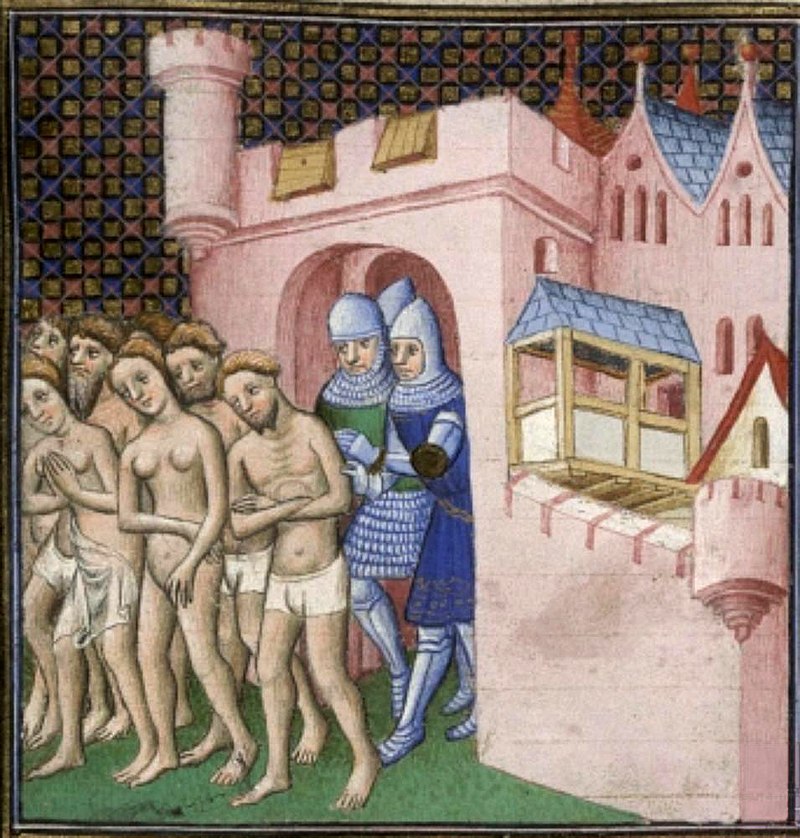

The next major target after Béziers was Carcassonne, which was now overflowing with terrified refugees. The Crusaders arrived on August 1, 1209 and by August 7 they cut the water supply. Raymond- Roger Trencavel, the viscount of Beziers and Carcassonne, tried to negotiate with the Crusaders but was captured and thrown into prison where he died soon afterwards Carcassonne surrendered on August 15. The people were spared death but forced to leave, clad only in their shirts.

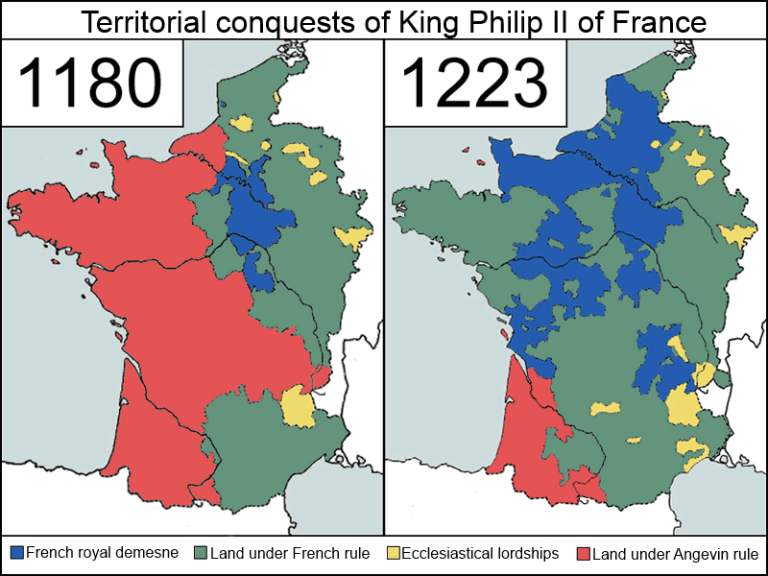

The Albigensian Crusade spurred the expansion of the Kingdom of France

Soon after the fall of Carcassonne, other towns in the area surrendered without a fight. By 1215, Simon had taken most of Occitanie, enriched himself enormously in the process and was appointed Count of Toulouse at the Fourth Lateran Council. As the crusade progressed, the conflict increasingly took on the character of a territorial conquest rather than a purely religious mission. The traditional Occitan nobility, many of whom had supported the Cathars or opposed the crusade, were dispossessed of their lands and titles. In their place, northern French nobles and the Catholic Church assumed control, altering the region’s political landscape and integrating it more closely into the French crown.

However the victory was an uneasy one because the inhabitants of Languedoc resented the brutal repression of the Crusaders. Soon afterwards Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse, and his son led a rebellion which recaptured much of the lost territory. The new French King Louis IX managed to restore control over the region in 1226 and the Count of Toulouse was forced to accept a peace treaty which bequeathed all his ancestral land to the French king at his death.

By 1229, the “official” crusade was over but the Cathars were still persecuted and marauding Crusaders continued to sack villages and murder innocent people. Between May of 1243 and March of 1244, the Cathar stronghold of Montségur withstood a siege but finally fell. In the massacre which followed, 200 perfecti were burned alive on a large pyre.

What was the legacy of the Cathars?

For an obscure 13th century bunch of medieval heretics, the Cathars left quite a footprint in the sands of history. The foundation of the mendicant orders (Franciscans and Dominicans) the creation of the Inquisition against heretics, and the clamp down on all forms of heterodox beliefs which did not concur with official Church doctrine. The Albigensian crusade also played its part in fostering the development of English parliamentary democracy by bolstering the fortunes of the De Montfort family and enabling the son of Simon de Montfort, the 5th Earl of Leicester to emerge as the leader of the baronial revolt against King Henry III which culminated in the first representative parliament being assembled in 1265 to discuss grievances against the English monarch.

The Foundation of the Mendicant Orders

Shortly after the Albigensian Crusade had been launched, sometime in 1209 Pope Innocent III had a dream which proved to be highly significant in shaping the future of the Roman Catholic Church. In his dream he saw the Basilica of St John Lateran, the cathedral church of the diocese of Rome, collapsing. A small man clad in peasant’s clothes stood supporting the church, a man whom Innocent recognised as somebody he had met a few months earlier – Francis, the leader of a group of followers who preached radical poverty. In his dream, Francis took the weight of the church and held it up with his shoulder. The church was straightened and set solidly on the ground. It had been saved.

It was because of this dream that Pope Innocent III, about a year after meeting with Francis and his men, officially recognized the new Order of Friars Minor or, as they became known, the Franciscans. Although the order didn’t play as active a role in directly combatting heresy as the Dominicans (established in 1216) , by preaching the virtues of leading a simple life of poverty and reverting to the ideals of the church’s original founding fathers, the Franciscans were able to penetrate the rapidly expanding townships of northern Italy and southern France and help defuse some of the criticisms levelled against the centralisation, opulence and corruption of the Roman Catholic Church.

The Black Friars and the Medieval Inquisition

it’s a sobering thought that if you were born in the 13th century and for various reasons had failed to fast during Lent,been inclined towards homosexuality or unbridled extra marital fornication, undertaken ground breaking scientific investigations, or decided to turn your hand to a bit of professional acting you would probably have been a victim of the Inquisition and ended up being burnt at the stake!

The origins of the Inquisition can be traced back to 1184 when Pope Lucius III issued a papal bull, Ad abolendum, which set out a programme to eradicate heresy. Some thirty years later in 1215 at the fourth Lateran Council, Pope Innocent III decreed that all bishops should hold an annual inquisition if there was any suspicion of heresy in the see. However, these Episcopal Inquisitions proved to be large ineffective. Other weapons were needed.

Forget about the Sixth Commandment

In 1231 Pope Gregory IX extended existing legislation against heretics and introduced the death penalty for them. These measures were initially intended to be a temporary means of rooting out Catharism. Inquisitorial commissions were granted only to friars, usually Dominicans, the mendicant order founded by Dominic de Guzman in 1216. The Inquisition effectively became the Dominican Inquisition. To mark the canonisation of St Dominic on his first Saint’s Day (4th August 1234) the bishop of Toulouse burnt a woman for her Cathar beliefs. After she had confessed to the bishop as she lay on bed sick with fever, she was carried to a field while still on her sickbed and consigned to the flames.

Tonsure and Torture

In 1252 the Inquisition was made permanent by Innocent IV when he issued a papal bull, Ad extirpanda, authorising torture, the seizure of goods and execution – all on the basis of minimal evidence.

All of the legal apparatus of the Inquisition was developed during this period. Prior to the Inquisition ecclesiastical courts followed the basic rules of modern justice: the accused were allowed to know the identity of their accusers, they were allowed legal representation, and in some places judgement was delivered by a jury composed of peers of the accused. The old bishops’ Inquisitions had been public hearings, but the new papal inquisitions were different: now secret hearings took place before in camera before clerical judges and prosecutors. Guilt was assumed from the start. There were no juries, no legal representation for the accused . There was no habeas corpus, no disclosure of any evidence against the accused, no appeal was permitted. Inquisitors were allowed to excuse each other for breaches of the rules – which meant that in effect there were no rules. There were secret depositions and anonymous accusations. Torture and unlimited detention in appalling conditions for those who failed to confess was the norm. People were incarcerated, chained up , with no light and given only bread and water. Dead people were tried along with the living and when found guilty their children were disinherited. At least half of their estate generally went to the Church – so that the Church had a material interest in obtaining a guilty verdict. Children and grandchildren of those found guilty were all debarred from holding any secular office.

In theory torture could be used only once, and was prohibited from drawing blood, causing permanent mutilation or causing death. Boys under the age of fourteen and girls under twelve were exempt. In practice there was no-one to enforce any of these safeguards, and they were all ignored. The accused were imprisoned, often for many months, before being examined. They were often kept in solitary confinement, in insanitary conditions, in a dark dungeon, and without adequate heating, food or water. This was deliberate, and designed to ensure that most of the accused would already have been broken by the time of their first interrogation. Only the strongest characters were able to face a tribunal of hooded figures who claimed to have heard witnesses and seen incriminating evidence. Most were prepared to admit anything, even though they did not necessarily know what the accusations were. Those who failed to admit their crimes were taken to a torture chamber and shown the instruments of torture. This too was designed to terrify and break them – the dark chamber, the horrifying instruments, the torturer-executioner dressed and hooded in black. If they still failed to admit their guilt they were then subjected to torture: men, women and children alike. Some people were tortured for years before confessing. Only the most strong willed could resist. .

Popular methods of torture included ‘squassation’ otherwise known as the torture of the pulley. Victims were stripped and bound. The cords were then tied around the body and limbs in such a way that they could be tightened, by a windlass if necessary, until they acted like multiple tourniquets. By attaching the cords to a pulley the victim could be hoisted off the ground for hours, then dropped. Whether the victim was pulled up short before the weight touched the floor, or allowed to fall to the floor the pain was acute. It was far worse than Pilates!

Rack and ruin

The rack was a favourite for dislocating limbs. Again, the victim could be flogged, bathed in scalding water with lime, and have their eyes removed with purpose designed eye-gougers. Fingernails were pulled out. Grésillons (thumbscrews) were applied to thumbs and big-toes until the bones were crushed. The victim was forced to sit on a spiked iron chair which could be heated by a fire underneath until it glowed red-hot. Branding irons and red hot pincers were also used. The victim’s feet could be placed in a wooden frame called a boot. Wedges were then hammered in until the bones shattered, and the “blood and marrow spouted forth in great abundance”. Alternatively the feet could be held over an open fire, and literally roasted until the bones fell out; or they could be placed in huge leather boots into which boiling water was poured, or in metal boots into which molten lead was poured. Since the holy proceedings were conducted for the greater glory of God the instruments of torture were invariably sprinkled with holy water!

With the methods of the Holy Office of the Inquisition and the fear of it deeply imprinted on the European psyche it is not surprising that within barely a century of its disappearance as an instrument of persecution, its methods were adopted (whether consciously or unconsciously) by modern day agents of totalitarian states such as Stalin’s secret police and the Nazi Gestapo.

The Rise of the De Montfort Family and the birth of English Parliamentary Democracy

Half an hour up the road from us in the Tarn et Garonne department lies the Chateau de Gramont. The 13th century chateau boasts an impressive crenellated fortification called the ‘Simon de Montfort Tower’.

Once owned by the 5th Earl of Leicester who spear headed the crusade against the Cathars, the fortified tower serves as a reminder of the historic links between the Anglo-Norman nobility whose estates spanned the English Channel in the early Middle Ages.

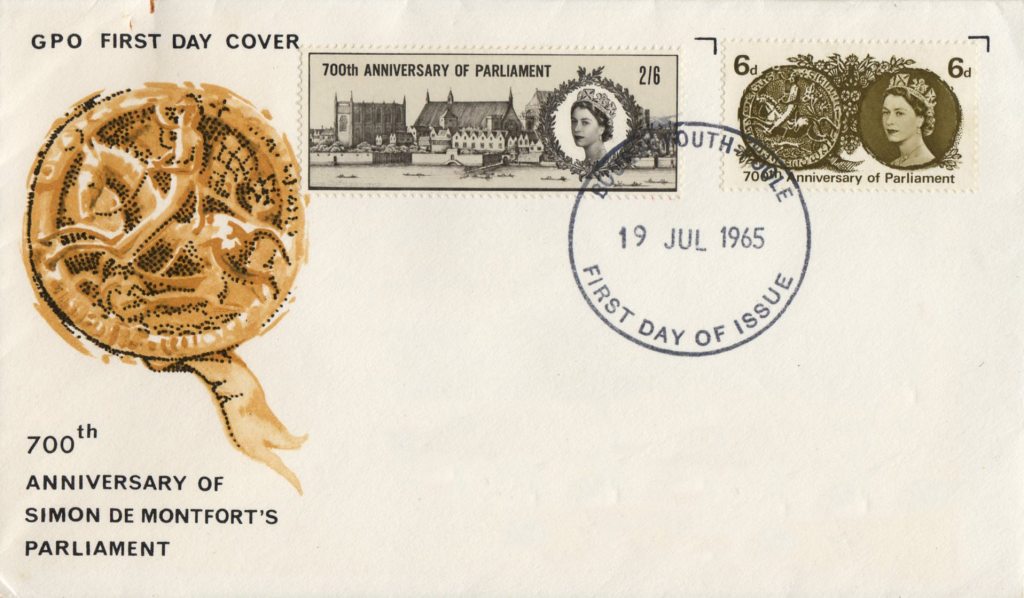

Although the 5th Earl of Leicester never visited his English estates, his son, Simon de Montfort the 6th Earl of Leicester did, and went on to play a fundamental role in the development of English Parliamentary Democracy. Perhaps inspired by his father’s deeds during the Cathar Crusade, his son led a baronial uprising against King Henry III that culminated in an assembly of Parliament in 1265 that involved the first representative debate against the monarch on subjects other than the raising of taxes.

The event was deemed so significant that the UK issued a series of postage stamps in 1965 to commemorate the 700th anniversary of Simon de Montfort’s parliament.

The Yellow Badges of Shame

As the Albigensian Crusade gathered pace, Pope Innocent III convened the 4th Lateran Council in 1215. The Council introduced measures which forced Cathars and Jews to wear yellow badges of shame on their clothes . For the Cathars this was a yellow cross while for Jews it was a yellow star of David to distinguish them from Christians.

These measures were subsequently enforced in France, England, Germany and later in Hungary. Some thirty five years later persecuted Cathars were forced to wear a yellow cross of shame to differentiate them from Catholics. 800 years later the Nazi regime in Germany resurrected the idea when they forced all Jews to wear the yellow stars of David during the 3rd Reich.

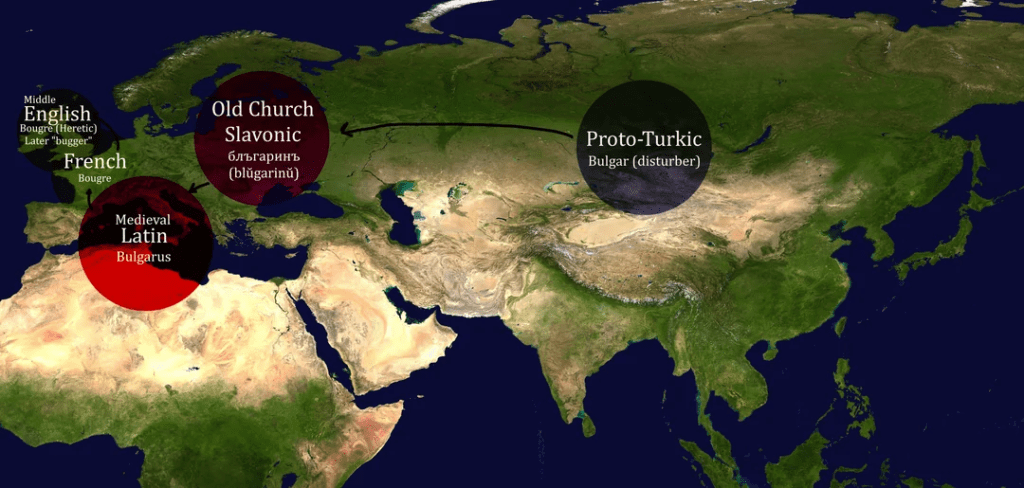

Beastly buggery

The Cathar movement gave rise to words for “heretic” in several languages: “Cathar” became Ketzer in German and ketter in Dutch, and Old French bougre (from a neo-gnostic sect known as the Bogomils based in Bulgaria, near the end of the first millennium, ) became “bugger” in Middle English. The French word also survives in the expression pauvre bougre = poor fellow, poor sod, and as an intensifier in invective like ‘bougre d’imbécile!’ [freely: bloody imbecile! or: f***ing idiot!].

So how did the sexual meaning of the word bugger originate? Well to the Cathars, reproduction was a moral evil to be avoided, as it continued the chain of reincarnation and suffering in the material world. It was claimed by their opponents that, given this loathing for procreation, they generally resorted to homosexuality and animal “husband”-ry. A charge of heresy levelled against a suspected Cathar was usually dismissed if the accused could show he was legally married. If not, then the assumption was that he was indeed a heretic or ‘un bougre’.

The Birth of English Protestantism

So heresy became equated with buggery in the 13th century which in turn led to a clamp down on all forms of ‘sexual deviancy’. In England such unorthodox practices were traditionally dealt with by ecclesiastical courts. Then Henry VIII, as part of a series of laws curtailing the power of the clergy in general, made it a capital crime under the purvey of civil courts with the Buggery Act of 1533, punishing “the detestable and abominable Vice of Buggery committed with Mankind or Beast”. Later jurisprudence limited “Mankind” to one specific type of act. The law remained on the books for centuries until superseded by a section of the general Offences Against the Person Act 1828 , itself in turn superseded by the Offences Against the Person Act 1861. Interestingly, simple consensual homosexuality remained a felony in England until 1967! And as for the Buggery Act of 1533, it was followed up in 1534 by the Act of Supremacy when Henry VIII asserted his supremacy over the Church in England and effectively told the Catholic Church in Rome to ‘Bugger orf’!

Old habits die hard.

It’s been a bit of a rambling blog, but hopefully its shed some light on the Cathars and their legacy. Before setting off on the Cathar Way later today, I’ll leave you with a final thought. Officially the last Cathar in the South of France (Guilhem Bélibaste) was burnt at the stake in 1321. However, unofficially, Cathars do still exist, meet and worship. A few weeks ago I was chatting to a friend who lives near us and mentioned that I was planning to walk the Cathar Way. At this remark he raised an eyebrow and, in a hushed voice, told me that one of the churches, near where he lives, occasionally holds Cathar services, although for obvious reasons they are never officially advertised. It seems that despite the best efforts of the Inquisition, old habits die hard in La France profonde!

Leave a reply to Rupert Cancel reply