We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time

T.S.Eliot- The Four Quartets : Little Gidding.

While I was walking the GR65 (Chemin de St Jacques) earlier this year, I bumped into a 75 year old Swiss walker in a gite I was staying in at Saugues in the Aubrac. Over supper I mentioned that I had just walked 42km from Le Puy-en-Velay. All the other walkers sat around the table were impressed, but the Swiss chap wasn’t. “Ach” he said to me with a grin, “42km is nothing. I remember when I was in the Swiss Army I once walked 100km in a day!”. That certainly took the wind out of my sails!

Apparently there are over 46 national trails in the UK covering 4,400 miles (7,000 km) and each year around 80,000 people in the UK complete one of these trails. As the adult population of the UK aged between 18 and 64 is around 42 million, this means that less than 0.2% of the population completes a national trail every year. The latest health survey of England in 2023 suggested that a staggering 64% of the adult population were either overweight or obese! In contrast there are over 7,000 gyms in the UK with over 10.7m members. Can we conclude that, by and large the UK is a nation of couch potatoes or gym bunnies, with a tiny minority of people who enjoy long distance walking?

This may be the case, but it’s interesting that there is a group of hard core long distance walkers in the UK who embark on extreme challenges such as walking from Land’s End to John O’Groats or circumnavigating 4,000 miles around the entire coast of the UK. The Charles III England Coastal Path is in the process of being set up and when completed It will go all the way around the coast of England stretching 2,700 miles!

If you want inspiration to get out and walk one of the national trails in the UK, I’ve drawn up a list of my six best travelogues about walking in the UK which I have enjoyed reading over the years. For those that want a real challenge, I can also recommend a book called ‘Out on your feet’ by Julie Welch which describes the 100 mile challenge, an annual showpiece event organised since 1973 by the UK Long Distance Walker’s Association. Held every year in a different part of the country, to coincide with the late May Bank Holiday, up to 500 people gather to walk 100 miles in 48 hours. I’m half tempted to enter the 100 mile Challenge next year (which takes place in Suffolk and passes through Framlingham, Woodbridge and Sutton Hoo) and show that Swiss hiker that 100km in a day is a trifle – real men walk 160km in 48 hours!

Even if completing a national trail in the UK or participating in the LDWA’s 100 mile challenge isn’t for you, perhaps I can tempt you to vicariously explore some of the UK’s best walks via 6 of the best books about walking in the UK which have inspired me since I first set off up Offa’s Dyke Path as 15 year old some 45 years ago!

1. Journey Through Britain – John Hillaby

John Hillaby’s book is an account of the long walk he took from Land’s End to John O’Groats in the mid-Sixties. More than half a century ago, so his walk is now an exploration of a fascinating point in British history – Britain in the Sixties was a very different country to the one we had now. There was still industrial infrastructure, and people were, I think, kinder and more compassionate. For all Britain’s faults – and there were many – it was a more hopeful time than now.

John Hillaby was a particularly fine writer, and Journey Through Britain was his masterpiece. He had other walking adventures and several more books, but none work quite as well for me.

Hillaby had intended to walk the length of the country just following our ancient trackways, a wonderful network of footpaths and bridleways, but this proved impossible. Many were blocked by overgrowth, were unwaymarked or deliberately obstructed. Those of us who were path campaigners at the time know that those were dark days in the history of access. So Hillaby was forced to take to roads and lanes from time to time, though there are plenty of accounts of path and wild walking too.

And what a route Hillaby took – along the Cornish coast, across Dartmoor, through the Somerset Levels to Aust Ferry on the Bristol Channel (the Severn Bridge hadn’t been completed.) Then up through the Black Mountains and Offa’s Dyke, through the Midland to the start of the then-fledgling Pennine Way. Across the Scottish borders and through the Highlands to the lonely lands of the far north.

Every chapter is fascinating to read, for Hillaby is very good at giving pen-portraits of the people he met along the way – poachers and transport-cafe waitresses, an itinerant and whisky-loving bagpiper, policemen and folk who were suspicious of walkers. He’s modest too – he often admits to losing his way, comes a cropper around Cranmere Pool on Dartmoor, has to make weary detours, finds the then new Pennine Way a bit of a trial. He walks through fine weather and foul, but every step shows a great love for this remarkable landscape.

Interestingly, John Hillably thought that he was going to be one of the last in a long line of literary tramps. He says that his book might be the ‘lay of one of the last’. He was wrong, of course; many have walked that long walk since and several more writers have written worthy books – I commend to you those by Chris Townsend and Hamish Brown. Journey Through Britain was not only a best-seller, but an inspiration to so many other walkers.

So if you want a beautiful armchair ramble, do sit down with Journey Through Britain, and relive John Hillaby’s own expedition through the spring and early summer of a year in the 1960s – across an England, Wales and Scotland that are still much the same, but in many ways so very different.

2. Two degrees west – Nicholas Crane

This is an account of an eccentric journey by an eccentric Englishman. Nicholas Crane is the man who, a few weeks after getting married, left his wife at home while he spent 18 months walking along the watershed of Europe from Galicia to Istanbul. Five years later, in 1997, equipped with his trademark umbrella and trilby hat, he was off again. This time the umbrella was in camouflage green, to help him stay concealed when he was trespassing.

He would have to trespass because he was aiming to cross England from north to south following the meridian line of two degrees west. This crosses the north-east coast at Berwick-on-Tweed, and leaves the south coast on the Isle of Purbeck west of Swanage. Giving himself strict boundaries of 1km either side of the line (the line which coincides with the Ordnance Survey’s Central Meridian), there were inevitably parts of the route with no public access. As well as private land there were lakes to cross, and rivers and motorways with no bridges, in his two kilometre corridor.

Crane’s route took him across the open spaces of Northumberland, the Cheviots, and the high Pennines, through small villages (but few towns), past isolated farmhouses, to the industrial townscapes of the Black Country. Emerging into the south of England he passed through gentler arable valleys and over bleaker chalk downs – including a crossing of Salisbury Plain – before negotiating Poole Harbour and finally reaching the end of his line at the English Channel.

But this is not a simple step-by-step story of a 578km walk, and if it was, it would probably be very boring. Although his account is chronological, it is not a diary – in fact the days and dates are hardly mentioned. Instead, he uses a number of techniques to keep our interest alive.

First, his research is extensive. There is a wealth of historical detail, much of it gathered beforehand, some gleaned on the way. Sometimes he presents this as brief snippets of information; at other times he goes into much more detail – for example, the story of Chance’s Glassworks in the Black Country’s Galton Valley, which was the factory which made the glass for the Crystal Palace at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

Then he uses a number of themes which recur throughout the account and give it continuity. So the canal builder James Brindley, and redoubtable traveller Celia Feinnes on her “Great Journey” through England in 1698, become companions who drop in and out of the walk. And the Meridian itself, at the heart of the story of the Ordnance Survey, is a theme which holds the whole enterprise together.

What distinguishes Crane from many other travel writers, especially in the “outdoor” genre, is his interest in and use of the people he meets along the way. As a self-confessed “harvester of stories” , he talks to anyone who will give him the time, listens to what they have to say, and slots their stories into his own.

The result is a book which achieves its continuity in the form of a verbal collage, analogous to Hockney’s photo-collages of the 1980’s, where a series of static images are arranged to give an impression of movement and change over time.

Crane writes with warmth and a laid-back, at times self-deprecating, sense of humour, not least in his descriptions of how he had to overcome some of the obstacles imposed by his meridional corridor. Setting out to wade or swim the Tyne, he festoons himself with ad hoc flotation aids (rubber rings, plastic footballs) and tentatively sets off, only to find the water never reaches his thighs. Another time he ruefully blames his mud- and cow dung-stained clothes for being turned away from a bed-and-breakfast.

Finding somewhere to sleep on the meridian sometimes gave him problems. One night near Cheadle, in the rain, unable to find a B&B, he tries to sleep on a ledge under a bridge arch. Defeated by the traffic noise, he sets off again in the dusk and rain for another three kilometres “over barbed wire, sodden meadows and ditches on a succession of public footpaths that had ceased through underuse to exist as imprints on the land” (p.164). Sitting disconsolately on a patch of grass in a deserted village, a woman in a car eventually asks if he needs help. Taking up the offer of a bed for the night at her farm, but of course having to decline a lift and walk instead, he ends the evening sipping whisky by the fire.

Many other incidents stay in the mind, not least the crossings of the more significant obstacles – Derwent Reservoir (thanks to the local sailing club), Salisbury Plain (thanks to the RAF and the Army), and Poole Harbour (thanks to the Royal Marines). But one of the most unusual aspects of the book is the extensive part – about 30 pages – describing Crane’s travels through the industrial West Midlands. Few walking guidebooks describe the streets, canal-sides, and waste ground of urban England, but Crane is as interested in these landscapes and their inhabitants as he is in the countryside. So we have a picture of a solitary, incongruous figure with rucksack and umbrella picking his way where no-one ever walks – beneath motorways, across canals on ancient iron bridges, ducking through dank passages under railways – and at the same time recounting the history of the engineers and workers who designed and built it all.

In the first part of the book, Crane is mostly non-judgmental about the countryside he is passing through, but by the time he reaches the south he is more inclined to criticise what he sees happening to rural England – supermarkets providing free buses and killing village shops, an intolerance of travellers on foot in the shape of overgrown and blocked footpaths and instances of hostility towards an admittedly dishevelled walker going about his lawful business. In a more negative moment he says “Most country people were welcoming and generous, but they lived in a rigidly controlled no-go zone, stripped of species and dulled by factory farming. . . .The English countryside was closed unless otherwise stated. Rustic enlightenment was tough on the nerves. When I wasn’t breaking the law, I was confined to a grudgingly conceded line across somebody else’s land”.

“Straight-line walking is a triumph of faith over expectation; believing in the unexpected rather than expecting the unbelievable”, says Crane . His unusual journey, linking people and places with nothing else in common except geographical accident, gives us a sympathetic and intriguing picture of present-day England.

3. Walking Home – Simon Armitage

This is a bitter sweet account of a penniless poet’s attempt to walk the Pennine Way from south to north and return home. During the day he would walk, and in the evenings he would stay with those he met along the way while earning cash by giving poetry readings.

“In many ways,” he says, “the Pennine Way is a pointless exercise, leading from nowhere in particular to nowhere in particular, via no particular route and for no particular reason.” The 256-mile route wobbles down the shoulder of Britain from Kirk Yetholm just over the Scottish Border to Edale in the Peak District, taking in the best and bleakest of the North along its way. Most people walk the route south-to-north, but Armitage chooses instead to walk towards Yorkshire, and home.

As he notes, Britain has always been full of poets striding the summits in search of something sensitive yet menacing to say about peat bogs or rosebay willowherb. Wordsworth had such a passion for walking that it was later calculated he managed over 185,000 miles in his lifetime. And even among those who don’t plan on turning their blisters into 14-volume autobiographical blank-verse epics, the old routes have become increasingly popular.

Some of these new strolls are old pilgrimage routes, some are military roads and some are just the paths that drovers used to get their beasts to market. Either way, the point of it all for modern walkers is neither livelihood nor penance, but the making of a personal journey with a ready-made narrative attached.

Armitage wanted that, but also, “to write a book about the North, one that could observe and describe the land and its people, and one that could encompass elements of memoir as well as saying something about my life as a poet.”

He posts a notice on his website asking for bed, board and company along the way, and as the date of departure edges closer, begins to have misgivings. “When I confide to a friend that I rate my odds as no more than 50-50, he says, ‘I admire your optimism.’”

By all the laws of prose and weather, things should start bad and then get better. Instead, things vary. Some days he is accompanied by a self-appointed escort of fellow poets and path-rangers. Sometimes he enjoys himself, other days he gets lost. Sometimes he meets those coming in the other direction: fell-runners, walkers “kitted out to withstand biological warfare or a chemical attack”, people whose job it is to keep very rare plants under round-the-clock armed guard.

Armitage is a lapsed geographer, and though he says he’s uninterested by the age of fells or the liquidity of stones, the whats and whys of his chosen landscape clearly begin to tell on him. On Cross Fell, “a truly terrible place… some abhorrent strain of that particular fell species, the Caliban version, illegitimate and monstrous,” he very nearly gives up.

In among the moors and lochs, he finds flashes of treasure – a remembrance of a summertime spent smelting lead ingots, the lady in a deserted shop in Middleton-in-Teesdale who offers him a new set of walking poles. He offers up his poetry to audiences avid or indifferent from Abbotsford to Hebden Bridge, stays in hostels, hotels and spare rooms, and is given in payment many things including corn plasters, HP Sauce sachets and a notice instructing him to “Watch Out for Dippers”.

Unlike other great walking books like Robert Macfarlane’s recent The Old Ways or Rory Stewart’s The Places in Between, Walking Home is neither scholarly meditation nor record of barely-human endurance. Armitage’s journey is more pedestrian than that; a manageable distance along a worn path through familiar faces.

But it’s exactly those things which make this book so lovely. There are a thousand blogs out there offering accounts of walking everything from the Mongolian Steppes to Deptford High Street, all of them filled with exclamation marks and epiphanies, and all of them completely unreadable.

But Armitage’s account is so observant, so funny and so intensely likeable you leave it wishing he’d picked a longer route. The dialogue is note-perfect and the jokes alone are worth the journey. And at the end of it all, Armitage has achieved far more than his stated ambition. Walking Home tells us not just about the bones of Britain, but about the connections still to be forged between people and print, and the everlasting power of an open heart.

4. The Old Ways – Robert Macfarlane

One of the finest nature writers of our time, Macfarlane is able to bring the world, to use a cliché, alive on the page or, as in this recent circumstance, in the listening. He is able to pull one into the landscape, its history and its place in the human imagination. His books are the product of a deep engagement with the subject at hand, a commitment that often takes years before the final text is complete. The Old Ways, subtitled A Journey on Foot is perfect walking companion because it is, more than anything, about walking—tracing paths and passageways—a book that is not about the destination but act of following the trail. A trail peopled with a collection of intriguing characters, living and long gone, for a path exists as evidence of the creatures who have passed on it before, even if lies hidden for many years or longer, waiting to be uncovered and tracked once again.

As ever, his eye is keen, his writing lyrical, and his affection for those he meets or travels with undeniable.

Divided into four sections, The Old Ways, begins in England, traversing different types of landscapes—paths, chalk, and silt— and then moves to Scotland where he travels traditional waterways, explores the Hebridean moors and then revisits his first mountains, the Cairngorms. This is where his grandfather had settled after a life of adventure, and where young Robert fell in love with “high country and wild places.”

It is also where his path crosses the ghost of Nan Shepherd whose intimate relationship with the same terrain is recorded in her masterpiece, The Living Mountain, a manuscript completed near the end of the Second World War, but unpublished until 1977. Macfarlane would not encounter her work until much later, long after the author’s death. But her poetic, deeply sensitive nature writing has no doubt informed his own. From Scotland, his journey moves abroad, to Palestine, Spain and Tibet, before coming home again to travel ancient paths and pay homage to poet and writer Edward Thomas whose footsteps guide him throughout this tribute to the powerful pull of the path.

5. The Green Road into the Tees – Hugh Thomson

One of the most challenging aspects of any author’s life is the way in which ideas can circulate in the ether to emerge from different pens at the same moment. It is impossible to pick up Hugh Thomson’s book, tracing the prehistoric Icknield Way that bisects England at a diagonal from Norfolk to Dorset, without being aware of Robert Macfarlane’s recently published The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot, which includes the path in its itinerary.

This route passes close to both writers’ homes, Thomson’s in the Thames Valley and Macfarlane’s in Cambridge. Both are at least partly inspired to follow it by Edward Thomas’s account of walking the Way, published in 1913; both were friends of the late nature writer Roger Deakin. There is even a moment when they both spend a night in the hills near Luton, Macfarlane sleeping in the “Neolithic dormitory” of a hill-fort, Thomson trespassing to Ravensburgh Castle. Perhaps they stumbled past each other in the dusk?

However, differences are immediately apparent in what propels these two protagonists. While Macfarlane is escaping the rigours of the Cambridge academic life, travel writer and film-maker Thomson is an inveterate wanderer, recently returned from Peru. It is the powerful strangeness of a jamboree in his local town, where a brass band is playing Abba’s “Dancing Queen” to tattooed farmers’ wives, that persuades him to set about exploring his own “complicated and intriguing” country.

His decision to walk is pragmatic: he has recently lost his driving licence, comforting himself with the idea that there is “nothing like being on foot to get the taste of a journey”. To add to his kitbag of troubles, he is shortly to be evicted from the barn he lives in near the banks of the Thames, in a village where he grew up river swimming and messing around in boats.

Peripatetic or not, he doesn’t hang about. “The cure for a hangover,” he explains, “was to keep drinking. The cure for jet lag was to keep travelling. I was on the train to Dorset the next morning”. He is an illuminating companion, his wide experience of the Inca heartlands a lens through which he deciphers Bronze Age Britain. Pausing only for coruscating condemnation of Prince Charles’s architectural folly at Poundbury, he strikes out from the coast for Wiltshire. Here he is at his best, explaining why Stonehenge should not be seen as an isolated site but instead as part of a wider “ritual landscape”, akin to that of the Inca in Peru.

Refreshing himself with Peruvian coca tea in order to let off Orwellian broadsides against aristocrats, bureaucrats, politicians and prelates, he is pulled towards a prehistoric epiphany at the site of “Seahenge” on the Norfolk coast. Frequently comic, his voice is original and engaging; proof that it is the walker, not the path, that counts.

6. The Salt Path – Raynor Wynn

The book tells the story of the author and her husband, Moth. After losing their home and business following a bad investment, and Moth’s diagnosis with a terminal illness, they decide to walk the South West Coast Path. This is England’s longest waymarked footpath, and runs from Minehead in Somerset, along the coasts of Devon and Cornwall, and finishes in Poole, Dorset; a distance of 630 miles. This book documents their progress as they walk, progress both geographically along the path and psychologically, as they come to terms with the changes in their lives.

This is a book that makes you think. Primarily, it makes you think about homelessness. About the people who become homeless, the circumstances leading to their homelessness, ways of coping with it, our reactions when we come face-to-face with homeless people, stereotypes, and above all, how we might cope when confronted with this ourselves.

It also makes you think about kindness. The kindness of strangers, in offering shelter and sharing resources. This might be the offer of a safe place to camp, sharing food when you have very little yourself or even offering to rent a flat to people you’ve only just met. Linking in with this, it makes you think about friendships. About the worry of becoming a burden, or the potential for people taking advantage when friendships are no longer between “equals”, but also about the more transitory, but still very real friendships which can arise from shared experiences.

In a world where we never seem to have enough time, it is about having almost nothing but. It is about grief, physical hardship, and loss. About being disconnected from society, and from family, and from the life you had before. Above all though, this is a book about the love of nature, of freedom, and of recovery and healing. It contains some wonderful, evocative descriptions of landscapes, the pleasure of watching a peregrine falcon soaring above you, of swimming in the sea, and of eating salted blackberries.

Fair warning – this is a book which can get you in the “feels”, so be prepared to have it pull on your heart strings in places. But it is also very uplifting, so let it reinforce your love of nature, restore your faith in human nature, and take you away to the wind-swept south coast.

It would be churlish not to give a brief mention to 3 other books about walking in the UK which are worth a look and focus on geology, pligrimages, recovery from depression and the hallucinatory world of 100-mile walking.

Walking the Bones of Britain – Christopher Somerville

Christopher Somerville has walked more miles than most but in Walking the Bones of Britain he has not only tramped the length of Britain; he’s also travelled back in time. It’s a journey of a thousand miles taken over a mind-blowing period of three billion years and his time travel began back in the last century when, as a teacher, he (naughtily) tore a geological page out of a classroom atlas. He had suddenly been beguiled by the colourful rippling layers which portrayed our oldest rocks in the top left and the youngest in the south-east: from the gneiss of the Outer Hebrides to the mud banks by the Essex marshes. Wouldn’t it be nice to walk through, across and over all those different ribbons of rock?

The map was then tucked away in a drawer for forty years until there was a suitable window of opportunity. Somerville had already wandered many of the places that caught his eye but now wanted to link them all together via a spider’s web of long distance paths, old drove roads, canal towpaths and a voyage down the Thames through the heart of London. Along the way, there’s geology under every footstep but also plenty of stories which connect our rocks to our wider culture. Our towns, our buildings, our food, our wildlife and our woods are all influenced by what happened all those eons ago. And the industrial revolution was fired by that dark matter known as coal.

Ironically, the author admits geology was a bit of a bore when he was at school. He struggled to get his head around laminated rhyolites and tuffaceous breccias, but that sneaky map helped open his eyes. Here, on Skye, was the crumbly escarpment of Trotternish; there were the loch-splattered wastes of Rannoch Moor. Here was the small but extraordinary fossilised forest in Glasgow; there were the lonely lead smelting sites in the Yorkshire Dales. Here was the deep shady gorge of Miller’s Dale in the Peak District; there was Northamptonshire’s Blisworth canal tunnel, where Cornish miners took twelve years to hack through a trifle of sandstone, limestone and mudstone.

The narrative helps demystify some of our more daunting geological technicalities and the nine-month journey is laced with humour and history. The immense timescales are sometimes difficult to fully comprehend but at least you’ll be pleased you weren’t out hillwalking when a meteorite smashed into the north-west coast of Scotland more than 1,000 million years ago!

On this Holy Island – Oliver Smith

What does an award-winning travel writer do when Covid restrictions stop him globe-trotting — in this instance, sparing us yet another slog to Santiago?

Oliver Smith pulls together a wonderfully eclectic series of visits within Britain, loosely linked by an elastic definition of pilgrimage as a “journey of meaning” — sometimes a literal journey, sometimes “conversations across time”. Thankfully, he is quite clear that “This is not a memoir of a troubled soul hoping to be fixed by the road.”

He likes to bring us to well-worn destinations from an oblique angle. At Lindisfarne — where he takes himself to the café rather than pay to visit the priory ruins — he writes about crossing the causeway barefoot at low tide, camping in the refuge hut as the waters rise. He takes us to Glastonbury through the history of an obscure well at the edge of town, and to Walsingham (the regional “homeland of Alan Partridge”) by the story of its little railway line, and the surprising communities that it connects to the shrine. Stonehenge he approaches through the rise and fall of the Free Festival, and the surprising part played by the Earl of Cardigan, hereditary keeper of Savernake forest, in bearing witness to its brutal suppression.

He is fond of the lumpy perspective that rough sleeping offers. On the Gower, he sleeps in the almost inaccessible sea-cave where the palaeolithic remains of the Red Lady of Paviland (actually a man) were discovered. Along the Ridgeway, he spends the night in a long barrow. On a tiny island on Derwent Water, associated with Beatrix Potter and St Cuthbert’s friend Herbert, his slumber is interrupted by a plague of mice.

The trudge out of Southwark on the Pilgrims’ Way to Canterbury, with its ancient echoes, is vividly described, as are the wrecked feet that make him pack up at Aylesford Priory. He does manage 27 miles across the Knoydart peninsula to the most remote pub in Britain, but it’s closed. “It seemed this pilgrimage had lost its shrine.”

His most unexpected destination is a football stadium, in a thoughtful and moving chapter about all that led from the Hillsborough tragedy to annual Anfield pilgrimages. “Liverpool became a Three Cathedral City on Hillsborough Sunday.”

On This Holy Island is pilgrim book and travelogue, Christian and pagan, history and legend, author’s journal and character-sketches. Some readers may have less patience than the author with neo-paganism, and there is a tendency to treat Christianity as another kind of folklore, with an unexamined elision of the holy into what is magical and mythical.

It is also entertaining and well-written, offbeat and informative. Smith is an interesting companion, though we know no more about him by the end than we did at the start. If the proof of pilgrimage is the return journey, we might heed the Stonehenge veteran who said: “real change could only be effected in the place that you most understood: home.” But that is over the book’s horizon.

A Walk from the Wild Edge – Jake Tyler

The remarkable true story of one man’s escape from the depths of depression through his 3,000 mile walk across the country.

When he set off in June 2016, shortly after his 30th birthday, he was two stone overweight and had a drinking problem. The walk would take him more than a year and a half to complete, and along the way he’d lose his walking boots, stagger onwards in his socks, and have his backpack stolen, containing every possession he needed.

And yet through the physical challenges – resulting in calves like rocks and ankle damage – came an emotional calm derived from the simplicity of nature. It was this, he says, that saved him. ‘It really felt like I was just walking it all off. I was completely winging it – I’d done no training – but I had this thing driving me.

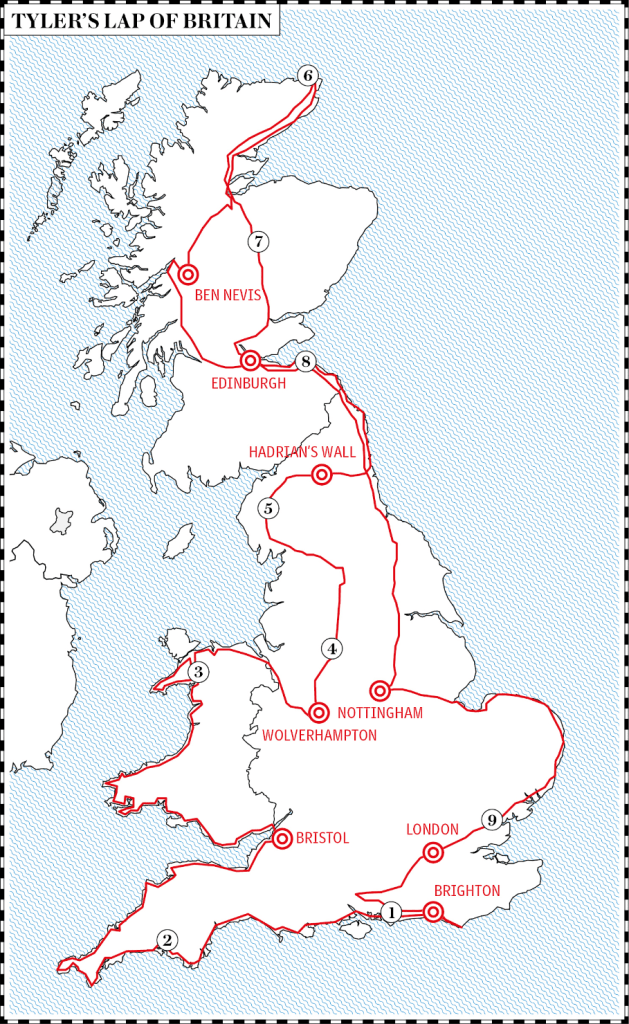

In an attempt to overcome his suicidal thoughts after he had been signed off work and returned to his mother’s home in Maldon, he came up with the idea of circumnavigating the British mainland. He bought a map of Britain from a local bookshop, spread it out on the living-room rug and, with a black marker pen, furiously circled every section of natural Britain he could see: national parks, areas of outstanding natural beauty, trails, beaches… ‘Anywhere that was green and didn’t have tangles of roads coming out of it,’ he explains.

Next, he drew a line connecting the circles, and what emerged was a giant loop of the country, starting at Brighton’s Palace Pier, then going via Cornwall, the Yorkshire Dales, East Anglia, and large swathes of Wales and Scotland, and finally back to Brighton for ‘a beer and a bag of hot doughnuts’.

Using Google Maps, he calculated that if he walked 13 miles a day, staying off roads where possible, the route would take roughly seven months to complete. He would sleep in a two-man tent but he budgeted for the occasional hostel on nights when the weather was particularly bad.

In all, he budgeted £5,000 for the entire trip, including kit and a daily allowance of up to £20, which he raised through a combination of crowdfunding and drawing on his savings.

Tyler was about as far from being a hardened explorer as you can imagine. He carried only a tent, a sleeping bag, a waterproof clothes bag (which he used as a pillow), two tops, a fleece, some socks and a compass (which he never used), plus a spare phone to keep in touch with his mother. His rucksack was otherwise filled with bread and packets of fruit and nuts from Lidl. He decided to buy one meal a day in a pub or café from his daily budget: ‘If I hadn’t eaten enough I’d feel it, and if I ate too much I’d feel it.’

The walk got off to a rocky start. On 27 June 2016 he set off, walking 10 miles out of Brighton to Worthing, but at the end of the day he was in such agony from his lack of training that he got drunk with a pub-manager friend.

The following day, after crashing overnight in the pub, he was too hungover to walk anywhere. He persevered, but those early weeks were a stuggle. The first 800 miles took him 82 days, much longer than planned, and by the time he reached the Severn Bridge and crossed into Wales, the weather turned.

By now, his tent was in need of repair and his mood was low, the setbacks mounting. ‘Bad weather, sore feet, stones in my boots, not knowing where I was half the time, the wind, going to the loo outside…’ And yet with every challenge, he became more confident.

One standout moment came in October, four months in. He had to cut through the town of Pembroke to continue his route on a coastal path and, after pitching his tent for the night in a clearing, he went off to treat himself to a toffee apple from a local shop. When he returned, absolutely everything had been stolen: sleeping bag, clothes, maps, spare phone.

Despairing and angry, he found a bed for the night in a local pub – and to his astonishment, a local woman, who had got wind of the theft via Facebook, spotted the stolen camping stuff in a bush near her house. She collected Tyler, drove him there and he recovered everything.

It was just one of many acts of unexpected kindness he encountered – like the time in the Brecon Beacons when a shop assistant in a camping store gave him a free display tent to replace his broken one, after he shared his story. It was this human kindness that kept him going, and kept him optimistic.

His 3,000-mile journey allowed much time for reflection. He finally completed the challenge in February 2018, some £3,000 over budget and more than a year later than planned. The walking itself took six months longer than he’d calculated (partly because he decided to stay with people he met for a couple of days at a time), plus he took a six month hiatus in the middle to take part in a BBC documentary to raise awareness around mental-health issues.

By the time he finished, much had changed. He not only felt different, but he looked different too – significantly more muscular and roughly two stone lighter.

Out on your feet – Julie Welch

For five years Julie Welch, a sports writer and marathon runner, edited the magazine of the Long Distance Walkers Association -a remarkably large group of people who meet up most weekends to undertake arduous walking challenges 20, 40 or 60 miles long. The highlight, (though others might well say nadir!) of the Walkers’ calendar has long since been the annual ‘Hundred’. First held in 1973, and every year since, its eclectic (but uniformly addicted) participants will walk a hundred miles, non-stop, within 48 hours – watching the sun set and rise again…twice.

The annual Hundreds both beguiled and allured Julie until the sports journalist felt herself powerless to resist; she decided she had to have a go herself. Out On Your Feet is the story of what happened: of the 50-mile walks she took part in to build up to the big day; the singular, admirable, often eccentric and above all tough-as-old-boots members of the long-distance fraternity; and finally the full wonder, pain, horror, exhilaration, even hallucination of walking a Hundred. (With fatigue as a constant travel companion, the mind will play tricks…)

Out on Your Feet sits halfway between such classic accounts of long-distance running as Born to Run or Aurum’s own bestselling Feet in the Clouds, and studies of utter mad Britishness like Eccentrics. Out On Your Feet is a book about walking by nice, normal people clad in boots and backpack, stopping to eat sandwiches and cakes – but who do it once a year for a hundred miles non-stop. And who suffer so egregiously during the whole experience that it makes them want to sign up as soon as possible to do it all again next year. Julie Welch edited the magazine of the Long Distance Walkers Association, a remarkably large group of people who meet up most weekends to accomplish arduously long walking challenges – 30, 40 and 50 miles long. Eventually she decided she had to have a go herself. This is the story of what happened: of the 50-mile walks she took part in to build up to the big day; the singular, admirable, sometimes eccentric and above all tough-as-old-boots members of the long-distance fraternity, and finally (as far as she can remember) the full wonder, pain, horror, exhilaration, even hallucination – from groups of nuns to children’s roadside picnics at 4am in the morning – of walking a Hundred.

All in all it’s a highly entertaining book which delves into a fascinating sub-culture that will undoubtedly baffle and inspire in equal measure.

And as for me – am I up to the challenge of walking a 100 miles over a weekend next year? I’d have to be mad – but then maybe I am!

Leave a comment