Men at some time are masters of their fates. The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves, that we are underlings.

William Shakespeare – Julius Caesar Act 1 Scene 2

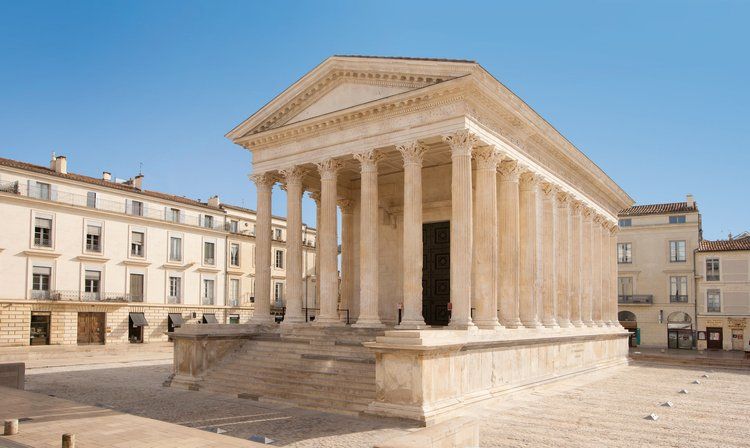

Dubbed the most Roman city outside Italy, the centre of today’s Nîmes combines the impressive vestiges of its Roman past with grandiose 18th century architecture and an impressive array of designer shops. There is clearly a fair amount of money sloshing around modern day Nîmes!

En route to my accommodation in the Diocesan house in central Nîmes (€22 for bed and breakfast) I walked through the impressive ‘Gardens of the Fountain’ and past the Roman temple known as ‘La Maison Carrée’.

Before heading off to Saint Gilles-du-Gard I decided to visit the Roman arena in the centre of Nîmes. It proved to be really worthwhile. In fact I could have happily spent an entire day looking around Nîmes.

The Roman arena is simply mind blowing. Built around 100 AD, shortly after the Colosseum of Rome, it is one of the best-preserved Roman amphitheatres in the world.It is 133 metres (436 ft) long and 101 metres (331 ft) wide, with an arena measuring 68 by 38 metres (223 by 125 ft).The outer facade is 21 metres (69 ft) high with two storeys of 60 arcades.It is among the 20 largest Roman amphitheatres of the 400 in existence. In Roman times, the building could hold 24,000 spectators, who were spread over 34 tiers of terraces divided into four self-contained zones.

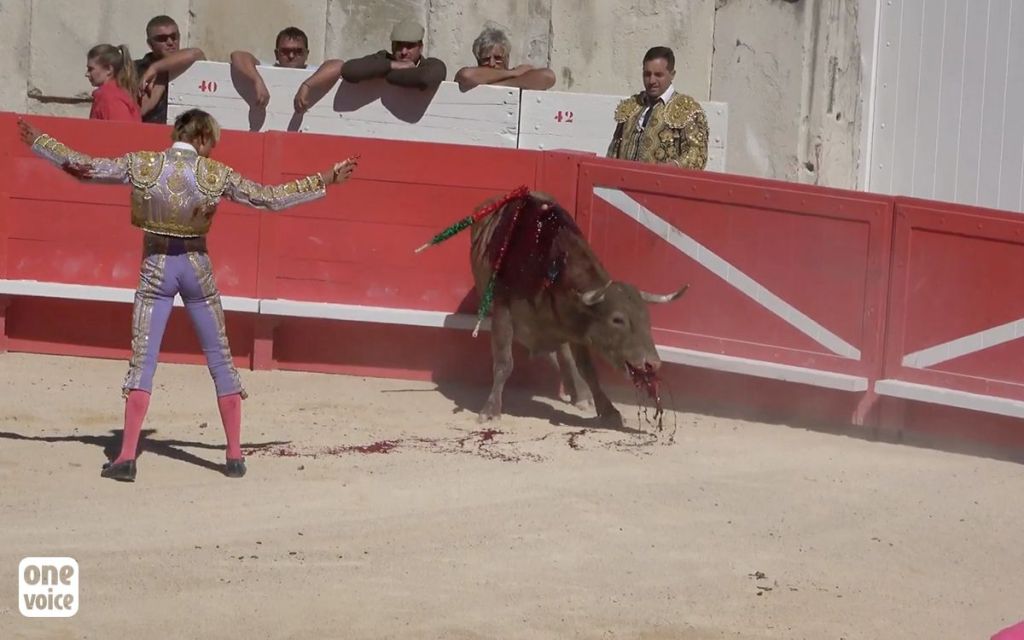

Arena (which means sand to absorb blood) was mainly used for gladiatorial contests rather than Christian martyrs being thrown to the lions.

It’s a sobering thought that gladiatorial combat with the threat of imminent death gave the ‘great and the good’ of the Roman Empire the same frisson of excitement as bull fighting which still features in the Nimes colliseum.

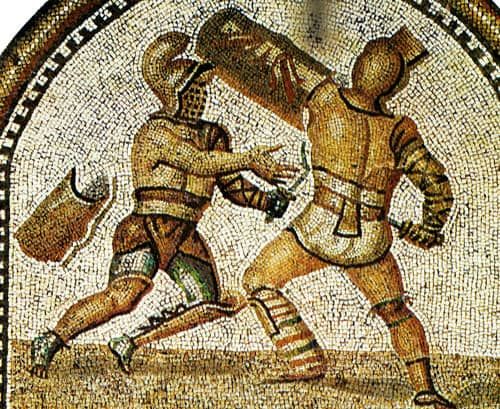

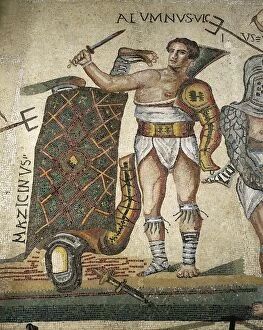

There is a lot of claptrap written about gladiatorial contests, aided and abetted by the Hollywood movie industry and the likes of Rusell Crowe in ‘Gladiator’.

Not all gladiators were brought to the arena in chains. While most early combatants were enslaved peoples and people who had committed crimes, grave inscriptions show that by the 1st century A.D., the demographics had started to change.

Lured by the thrill of battle and the roar of the crowds, scores of free men began voluntarily signing contracts with gladiator schools in the hope of winning glory and prize money. These freelance warriors were often desperate men or ex-soldiers skilled in fighting, but some were upper-class patricians, knights and even senators eager to demonstrate their warrior pedigree.

The spectacles proved hugely popular, and by the end of the 1st century B.C., govrnment officials began hosting state-funded games as a way of currying favour with the masses.

Deadly gladiator duels in Rome’s Iconic Colosseum, Hollywood movies and television shows often depict gladiatorial bouts as bloody free-for-all, but most fights operated under fairly strict rules and regulations. Contests were typically single combat between two men of similar size and experience. Referees oversaw the action and probably stopped the fight as soon as one of the participants was seriously wounded. A match could even end in a stalemate if the crowd became bored by a long and drawn-out battle, and in rare cases, both warriors were allowed to leave the arena with honor if they had put on an exciting show for the crowd.

Since gladiators were expensive to house, feed and train, their promoters were loath to see them needlessly killed. Trainers may have taught their fighters to wound, not kill, and the combatants may have taken it upon themselves to avoid seriously hurting their brothers-in-arms. Nevertheless, the life of a gladiator was usually brutal and short. Most only lived to their mid-20s, and historians have estimated that somewhere between one in five or one in 10 bouts left one of its participants dead.

The advent of early medieval Christianity marked the end of these events, prompting the transformation of the amphitheater into a fortress and subsequently a walled town.

After my tour of the amphitheatre, there was just time for a spot of shopping. Fearful that after two weeks ‘on the road’ without a change of clothes I might be carrying the fragrance of a greek wrestler’s jockstrap, it seemed a good idea to invest in a new shirt and pair of shorts for my visit to the Hotel d’Angleterre in Le Grau-de-Roi.

I met Périne at breakfast in the Diocesan house in Nîmes. She was also walking to Saint Gilles-du-Gard and subsequently planning to walk on to Le Grau-du-Roi.

The walk from Nîmes to Génerac was fairly uneventful. The terrain was flat and mostly on tarmac. With my boots falling apart at the seams, I was grateful for the easy going walk.

Shortly after 2pm I reached Génerac. Périne was sitting outside in a café. I joined her for a coffee and we spent the afternoon walking together to Saint Gilles-du-Gard.

We reached Saint Gilles-du-Gard shortly after 4pm and checked into our gite just outside the abbey which houses the relics of Saint Gilles.

Besides myself and Périne, there were four other pilgrims staying in the gite which was locatedin a cellar. It was cosy although I hoped there wouldn’t be too many snorers in close proximity.

I took a quick tour of the abbey and visited the relics of Saint Gilles in the crypt. For what had once been the fourth most popular pilgrimage in Europe during the middle ages (after Compostella, Rome and Jerusalem) it was a strangely underwhelming experience mainly because both the town of Saint Gilles and the abbey, were largely deserted.

Back at the gite, the proprietor, who looking after the place for a couple of weeks, invited us all to join him for an apero. A pizza had been laid on, a bottle of rosé was opened and the seven of us spent the next couple of hours swapping anecdotes about walks and pilgrimages we had been on.

Just after 9pm I decided it was time to turn in for the night. I’d double checked the distance for tomorrow’s last stage to Le Grau-de-Roi and discovered to my consternation that it was not 32km but 40km.

I would need to leave at the crack of dawn if I was to reach Le Grau-du-Roi before nightfall, take in a tour of Aigues-Mortes and buy some new clothes to gain entrance into the Hotel d’Angleterre. Sadly they hadn’t had anything suitable in my size in Nîmes!

Like the chemin, life is full of ups and downs but as the old saying goes – always follow your dreams because they know the way.

Leave a comment